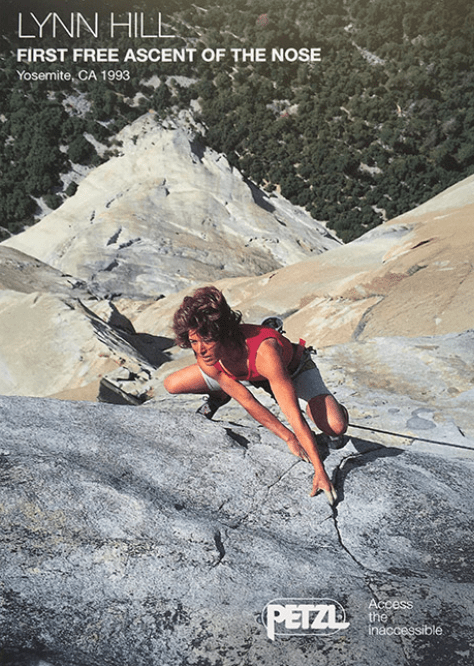

In 1993, Lynn Hill became the first person to free climb Yosemite’s El Capitan route, “The Nose,” in just one day. She was a pioneer in the sport of outdoor climbing, and a world class competitive climber, winning thirty international titles. The 90’s climbing community was hyper-masculine and predominantly white, even more so than today. Climbing was a culture of white men “defying” societal norms, spending their days carefree in the outdoors. They were considered climbing traditionalists, the quintessential “dirtbags.” And although they rejected the life of a job and a family, it didn’t make the sport more welcoming for non-male and non-white athletes who also wanted to push back against the typical lifestyle. After Hill’s ascent, male climbers with bruised egos spewed excuses for why they hadn’t completed the feat she had, claiming her accomplishments came merely from her “small fingers.”

As Hill’s popularity grew, she began going on talk shows, documentaries, and sports TV. In 1989, she was invited on David Letterman. An intrigued audience watched as the two climbed a small indoor rock wall, and the room filled with an occasional burst of applause. Despite Letterman introducing Hill as the “best rock climber in the world” he spewed objectifying and sexualizing jokes. As Hill set up Letterman’s belay device, he pulled on his shirt collar, signaling it was “getting hot.” He mentioned her outfit multiple times, stating, “You have a lovely little outfit on” and “I wish I had an outfit.” Hill’s strength and passion was like no other athlete in the climbing scene and her talent was disregarded, thrown back at her as a demeaning joke. When women succeed in a skill dominated by men they are often infantilized or sexualized to diminish their accomplishment. Sexualizing Hill was a way of perpetuating this idea.

As a girl in sports, I am very aware of the emphasis placed on physical attractiveness. In the fall of eighth grade, I started bouldering, and joined the competitive team a few months later. I hadn’t done a sport since I quit gymnastics two years prior. My failure to continue gymnastics was a result of my deep self-consciousness around my body. I feared taking my coat off with my leotard underneath. I looked at my body up and down, pointing out flaws in my own mind so others wouldn’t have to. Every Tuesday and Thursday I begged my mom to let me stay home, a routine she didn’t appreciate.

Just like the talk show jokes, or “male gaze” depictions in the media, I couldn’t escape society’s grasp. In Monika Radojevic’s “To Be A Woman” from her collection of poems, Teeth In The Back Of My Neck, she writes, “You must have a skeleton made of wire, to contort and bend your way around others.” I felt for a while that I did have that wire. As a product of society’s constant perpetuation of sexism, I was delicately crafted to adjust to others’ needs. Outside of rock climbing I felt I couldn’t be too muscular, and as I started to see my body change, I anticipated I could no longer be a reflection of what others wanted to see. Although I wanted to get stronger, I felt the push and pull of society’s conflicting expectations. Anything less than the standards of others desires would mean that I was not enough. I was focused on how others perceived me, when all I really wanted was to improve at a sport I cared about.

Joining the climbing team was the first time I pushed through that cloud of self-doubt. It connects me with athletes who promote self-confidence and celebrate others’ success. But as a woman I experience the burden of having to prove my talents in order to gain respect, where men are automatically given respect. It’s not that the people I surround myself with make me feel this way, but that the culture itself is still embedded in hyper-masculinity. The male ego is prevalent in climbing, where a lot of my male teammates brag about finishing a climb, or don’t admit when they’ve fallen due to lack of strength or misread climbing beta. In contrast, the women on my team, including myself, apologize for standing when we aren’t even in the way. The thought of our very existence in this male dominated space seems like something to apologize for.

My experience based on gender, race, sexual orientation, and the way those intersect, inform how I view and interact with the sport. My identity as a woman has changed the way I have experienced it, but as a white person in a predominantly white sport I’ve never had to experience the deeply embedded racism that exists within the community.

The elitism and general financial inaccessibility of climbing gyms make it a sport much more inaccessible for lower-income communities of color. The origins of the outdoor industry have emerged from racist histories, as the government pushed Indigenous people off their land, and turned what was once home to some into merely a space of adventure for white people. Colonialism built the industry. As government leaders created the National Park system, they claimed wilderness needed to be “tamed.” Even once the National Parks were open, people of color still did not have access to outdoor spaces because of the government’s blatantly racist regulations.

How do we dismantle ideas of sexism and racism that have been ingrained within the climbing community? Can we ever make climbing accessible when it was built on these systems of oppression?

Audre Lorde, self described as a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” and radical feminist, professor, and writer, beautifully articulated what she deems the “master’s tools.” In her piece “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” she writes, “What does it mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy? It means that only the most narrow perimeters of change are possible and allowable.” Lorde highlights that the tools used in our society’s patriarchal system are the same tools many use of us use in our feminist work. Yet real change is not possible unless we redefine the system, creating our own tools. Lorde’s words can be used as a blueprint for change.

Organizations that break the system and promote access for women and people of color are pushing back at the historic strain of whiteness and maleness in the outdoors, transforming this community. Memphis Rox is a climbing gym founded in 2018 in Memphis, Tennessee, a predominantly Black city. Regardless of an inability to pay, the gym never turns away anyone. It’s the first non-profit climbing gym of its size, and it reimagines the way we view currency. Memphis Rox changed the system, as no other climbing gym has taken this approach. I would argue that it even dismantles the master’s tools, reimagining the way we see rock climbing.

Lynn Hill’s pure talent helped push the start of a larger movement, one that has expanded the community of climbing. Hill once said, “I never let the industry’s desires and people’s desires pull me away in different directions. Climbing is for me.” We must change a system built for others rather than let the system change us. Rock climbing must be a skill accessible to those who have been told it is not for them.